Substance that transforms into a conductive polymer using the body’s own chemistry could improve implantable electronics

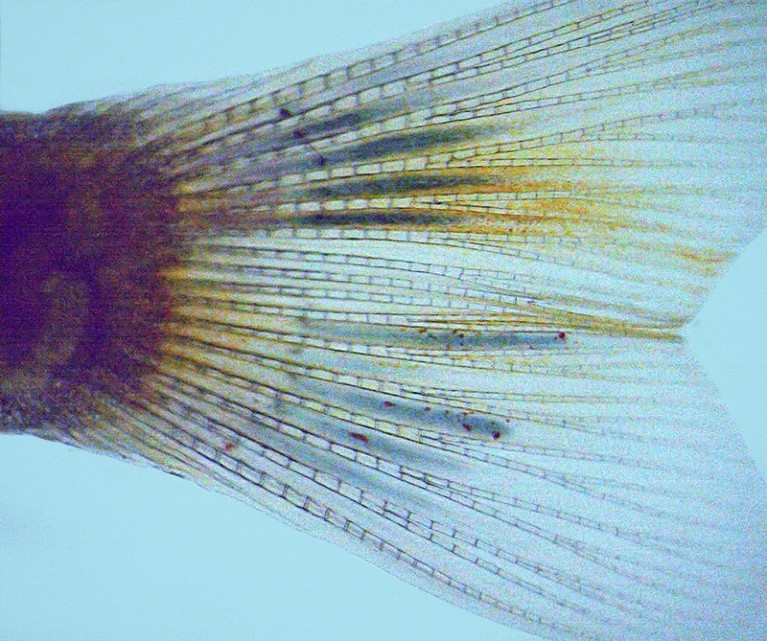

Conductive polymers (blue) formed in the tail fins of living zebrafish.Credit: X. Strakosas et al./Science

An injectable gel tested in living zebrafish can use the animals’ internal chemistry to transform into a conductive polymer.

The discovery, reported on 23 February in Science1, could lead to the development of electronic devices that can be implanted into body tissues such as the brain without causing harm.

When the gel is mixed with the recipient’s own metabolites — chemicals generated by the body’s processes — a chain reaction turns it into a solid but flexible material.

“We are performing a lot of experiments with these materials to grow electrodes and electronics around cells,” says study co-author Magnus Berggren, a materials scientist at the Linköping University in Sweden. He adds that the work could ultimately improve technologies for deep-brain stimulation, for example, or help damaged nerves to regrow.

Internal electronics

Electronic devices or circuitry that can be implanted in the body have many potential applications in medicine and research, such as helping the brain to communicate with prosthetic limbs, or even enhancing memory. But conventional electronic materials can cause inflammation or scarring, and they often deteriorate inside living tissue and eventually stop working.

The brain-reading devices helping paralysed people to move, talk and touch

Although there has been progress towards developing soft, flexible electrodes, it is difficult to get them into the body in a non-invasive way, says Berggren. If you want to insert something deep into the brain, for example, “you will basically make it cut all the way through”, he says.

Berggren’s team wanted to create a material that was conductive, but stable in the long term, non-toxic and of a consistency that allows it to be injected.

The mixture they developed contains the chemical building blocks for a conductive polymer, along with enzymes. When injected into living tissue, the gel reacts with the common metabolites glucose and lactate, which causes the gel to polymerize into a much firmer — although still soft — material. Working with a group led by chemical biologist Roger Olsson at Lund University in Sweden, the researchers used this approach to generate polymer ‘electrodes’ inside the fins and brains of living zebrafish (Danio rerio). They also used it in the nervous tissue of leeches and in muscle tissue from chickens, pigs and cows.

Because the material doesn’t polymerize until it is inside the body, and is “compliant, soft and biocompatible”, it eliminates mechanical differences between typical electrode materials and living tissue that make some medical implants so invasive, says Timir Datta-Chaudhuri, an electrical engineer at the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research in Manhasset, New York.

International Research Awards on Organic Chemistry

visit : organic-chemistry-conferences.sciencefather.com/awards/

Award Nomination : organic-chemistry-conferences.sciencefather.com/award-nomination/?ecategory=Awards&rcategory=Awardee

No comments:

Post a Comment